For a nation once ravaged by civil war, heritage architecture may be one of the best ways to preserve and honor Cambodia’s rich culture and history. At the forefront of many structures is Vann Molyvann, and today marks his fourth death anniversary.

Born in Kampot Province, less than three hours southwest of Phnom Penh, Vann Molyvann was able to study abroad in Paris, France, through a scholarship.

Initially enrolling in law, he shifted to the School of Fine Arts in Paris and pursued architecture instead. This made him the first fully qualified Khmer architect when he returned to his homeland in 1956—three years after Cambodia gained independence from France.

Shortly after, he was appointed as State Architect and as the Head of Public Works by Prince Norodom Sihanouk. Vann was thus instrumental in widespread infrastructural growth and development throughout the Kingdom.

Cambodia’s Golden Age of art, infrastructure

One of his earlier projects was the Council of Ministers Building along Russian Boulevard, which was sadly demolished in 2008 together with the Preah Suramarit National Theater and Exhibition Hall, also known as the Bassac National Theater. The latter had been ravaged by a fire in February 1994, in the middle of initial renovation efforts.

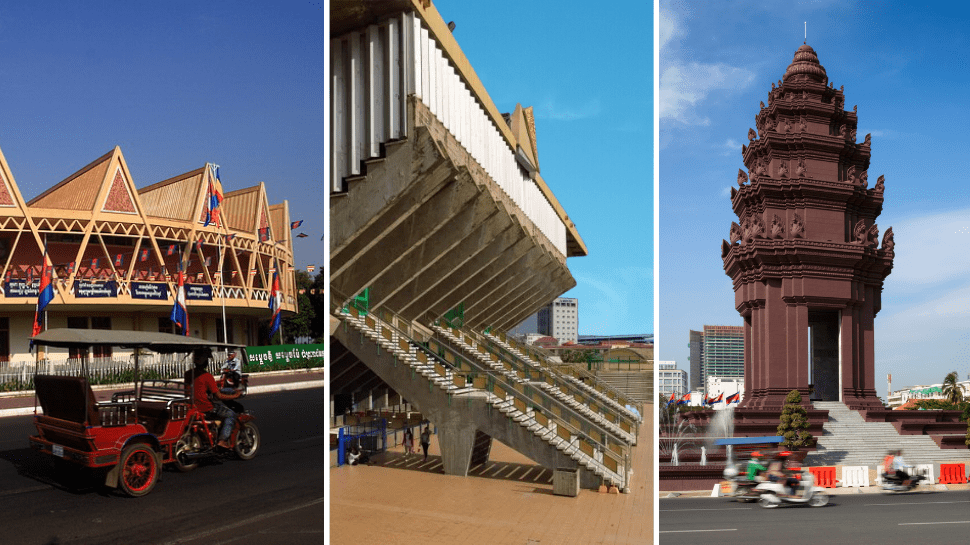

He is also the designer behind the Independence Monument, which was unveiled in 1958.

The Chaktomuk Conference Hall, an impressive, fan-shaped structure that’s a short walk from the Royal Palace and overlooking the Tonle Sap River, was finished in 1961.

The Olympic Stadium was built in 1964 with a total capacity of 60,000. Sold to and redeveloped by a Taiwanese firm Yuanta Group in 2000, the stadium still stands just westward of Preah Monivong Boulevard.

Speculated to have been built for the 1963 Southeast Asian Games, it never got to host this as the event was cancelled due to political uprisings in Cambodia. It did, however, have a diplomatic role in the 1966 FIFA World Cup for a match between North Korea and Australia.

The stadium was perhaps Vann’s greatest work, featuring not only Olympic-standard facilities but also impressive architecture: daring concrete overhangs, and a water management system that incorporated into its design the moats and channels of the Angkor era.

Even Lee Kuan Yew, then Singapore’s prime minister, invited Vann to help plan a new Singapore after he led a delegation to Phnom Penh in 1967. However, Vann turned the offer down.

1968 marked the opening of the Bassac Theater, which resembled a large ship along the Bassac River. It was a landmark venue for musical and stage productions with its wide stage and ideal acoustics, complementing Cambodia’s “Golden Age” —a time when the Kingdom brimmed with creative exploration, including in the areas of film, art, and music.

Architect, interrupted

Vann’s projects number over a hundred, including the port of Sihanoukville, the Royal University of Phnom Penh, many Cambodian embassies abroad, and his own private residence. However, this vibrant period in Khmer history dimmed when the Khmer Rouge took over the state.

He was able to relocate with his family to Switzerland, serving various consultant posts for the United Nations in the two decades that followed. However, the genocidal regime took its toll on Khmer infrastructure and tangible culture, in addition to ravaging human life.

While the Bassac Theater itself was minimally affected, a mere remnant remained after the war from over 300 artists who would regularly perform at the venue. The Olympic Stadium, originally a destination for recreation and sports diplomacy, was turned into an execution site.

In the early 1990’s, Vann returned to Cambodia, immediately serving his national as President of the Council of Ministers and as Minister of Culture, Fine Arts, Town and Country Planning. He was also a founding leader of the APSARA Authority, a multi-party organization that serves to research and manage land use of the ancient Angkor Wat temples.

However, his hand in the government was short-lived as there was a new distaste for anything built before 1979, when the Khmer Rouge was defeated. This may also be why many of his projects have not been spared demolition, though efforts like the Vann Molyvann Project exist to preserve and document his works.

Vann completed a doctorate on the history of Southeast Asian human settlements, and released several Khmer publications detailing the modernization of Cambodia. For a time, he was also involved in the leadership of the Royal University of Fine Arts.

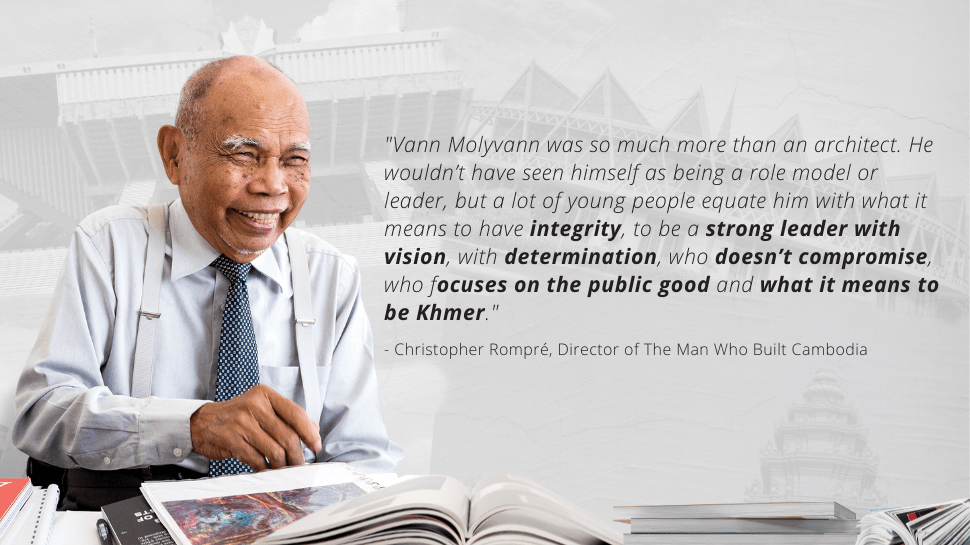

This is only fitting, as for many young artists and architects, learning of Vann Molyvann grants them with a Khmer role model who has proven that one can develop new buildings by merging foreign concepts with Cambodian elements.

The Rise of New Khmer Architecture

“Modernity should not be inspired superficially by Western ideas that destroy all trace of the past,” Vann had said. “New buildings should bring tradition and heritage back to life.”

Vann exemplified a style of architecture that draws on the Kingdom’s culture and heritage, while incorporating modern structures and materials. It is described by Archictectuul as a blend of Bahaus and European post-modernism adorned with Angkorian elements.

Developed during the period between Cambodia’s independence and the civil war outbreak, the style not only defined the post-colonial architectural fabric of Cambodia, but also fostered safe public spaces and inclusive social gathering as central to urban planning.

It is called the New Khmer Architecture movement, and while the country’s urban landscape has been shifting rapidly, there yet remains hope in preserving these heritage structures.

Vann Molyvann’s iconic Phnom Penh home, “characteristically elegant and meticulously designed,” is now being offered as a rare opportunity to own a historical home. Built when he was at his most experimental, the family occupied it even after the war, until moving to Siem Reap in 2014.

With a wealth of contributions to Cambodia’s architectural landscape, Vann is one of the most prominent figures in Khmer culture and truly a figure to celebrate. Having passed away at the age of 90 in his Siem Reap home, his legacy is honored by those intent on preserving heritage architecture, including his personal residences.